An early draft of a paper, blog post, grant proposal, or other piece of technical writing typically has many problems. Some of these are high-level issues, such as weak motivation, sections in the wrong order, or a key description that is difficult to understand because it lacks an accompanying figure. These problems need to be identified and fixed, but this is just about impossible as long as the text is crappy and drafty. All of the little problems — run-on sentences, filler words, paragraphs that switch topics without warning, etc. — tend to gang up and make it hard to see the big problems. In contrast, when individual sentences and paragraphs are clear and polished, high-level problems often just jump out at the reader, making them far easier to fix.

The process of writing (or my process, at any rate) ends up something like this:

- Write a rough draft.

- Edit until a high-level problem becomes apparent.

- Fix the high-level problem.

- Go back to step 2 until there’s nothing left to fix or the deadline arrives.

This process works, and it is the only way I know to produce good writing. However, the virtuous cycle can’t even get properly started if the writer is bad at copy editing: the process of fixing low-level bugs in writing. This is an absolutely fundamental skill, and if I could wave a wand and make students better at just one part of being a writer, I would choose copy editing.

Alas, we have to get better at copy editing the hard way: by practicing. Start by acquiring a half-baked piece of writing from someone else and trying to improve it. Something short like a cover letter for a job application or even an email would be good to begin with, and you can work up to longer pieces. It’s best to use someone else’s text: since you won’t be attached to it, your editing can be merciless. Just go over and over it until there’s nothing left to change; it can be a pleasure to beat a piece of text into shape this way (years ago I collaborated with a somewhat wordy colleague on a grant proposal, and secretly had a hugely enjoyable time making his text clearer and about half as long). When you’re done, give the edited piece back to its author and see what they think of your new version. This part isn’t necessarily fun, but it’s important to get feedback. Do this again and again.

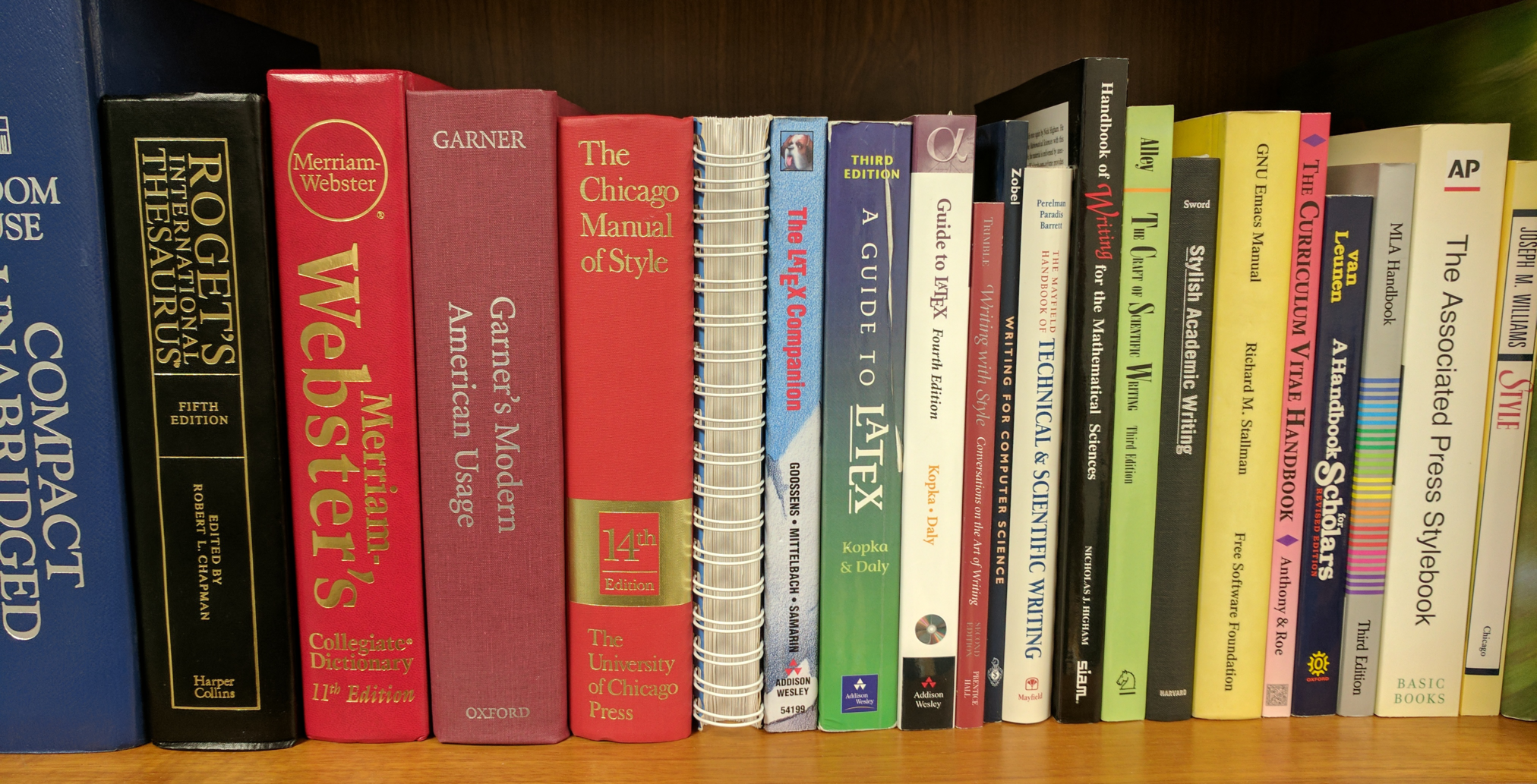

While practice is important, nobody should be expected to intuit the principles of copy editing: we require some outside help. There are numerous books; I’ll briefly describe two that I recommend.

The first book is Copy Editing for Professionals. I really love this book: it’s hilarious, informative, and distills decades of hard-won wisdom. On the other hand, there is material in there that, as a technical writer, you’ll need to ignore: it is mainly written by and for people who work at the copy editing desk of a newspaper or magazine. Even so, in my opinion this book is completely worthwhile for technical writers.

My second book recommendation is Line by Line. I’ve read a lot of books about writing and this one was easily the most influential; it opened my eyes to a rich collection of rules, guidelines, and conventions for structuring written English that I only dimly remembered from school, or was never taught at all. I suspect many others will have the same experience. Line by Line is not remotely an easy book, but it gives us what we need: clear, actionable advice about writing, accompanied by numerous good and bad examples. Technical people may appreciate Cook’s view that the work of a copy editor is largely mechanical: she is explicitly trying to teach us algorithms she developed over decades of experience as a professional copy editor.

Writing is a crucial skill, but nobody is going to fix your stuff: you’ll have to do it yourself. Making things worse, we do a very poor job teaching people to copy edit. The secret, insofar as there is one, is to seek out resources such as Line by Line and Copy Editing for Professionals, and to combine the kind of high-grade advice that they provide with a lot of practice, ideally augmented with feedback from someone who is already good at copy editing.

6 responses to “You Might as Well Be a Great Copy Editor”

Alas, our minds automatically fill in gaps and cover over mistakes when we read.

Especially reading our own writing.

If you’re a fast reader, your mind does this for you, allowing to skim and focus on the essence.

If you’re writing, this is a disaster. You can blindly skim passed your own mistakes _every_ time.

Solution?

Read aloud.

To your dog if need be.

The process of vocalizing forces more of your brain to be involved.

Your finite breath forces sentences to fit within your lung (and hence also brain) capacity.

Feed back from your ears tells you, ‘Hey! that sounded pretty bad….”

I edited technology books early in my career (gulp, 25 years ago) and the publishing company issued all of us a copy of Line by Line. I’m pleased to see you recommend it too!

to try -> trying

If I could recommend another book it’d be “Bird by Bird”. It’s not directly about academic writing, but many of the same principles apply and it greatly helped me.

https://boook.link/BirdbyBird

I also agree with John Carter — reading aloud is a very good technique for finding mistakes you’d otherwise overlook. In programming we do something called “rubber ducking”, where we explain what we are working on to a rubber duck (or other inanimate object) while debugging.

John: this is a great idea!

Jim, I have not seen a lot of people recommending this book, this is great to hear!

Thomas: thanks, fixed.

Cenk: thank you!

I’m not quite sure if what is described in the blog is copy editing or rather line editing. From my understanding, copy editing has to do with grammar, usage, and style only, whereas line editing has to do with making individual sentences or paragraphs better. An overly long and confusing sentence could still be grammatical and use en-dashes appropriately.